contents

how a ribbon works

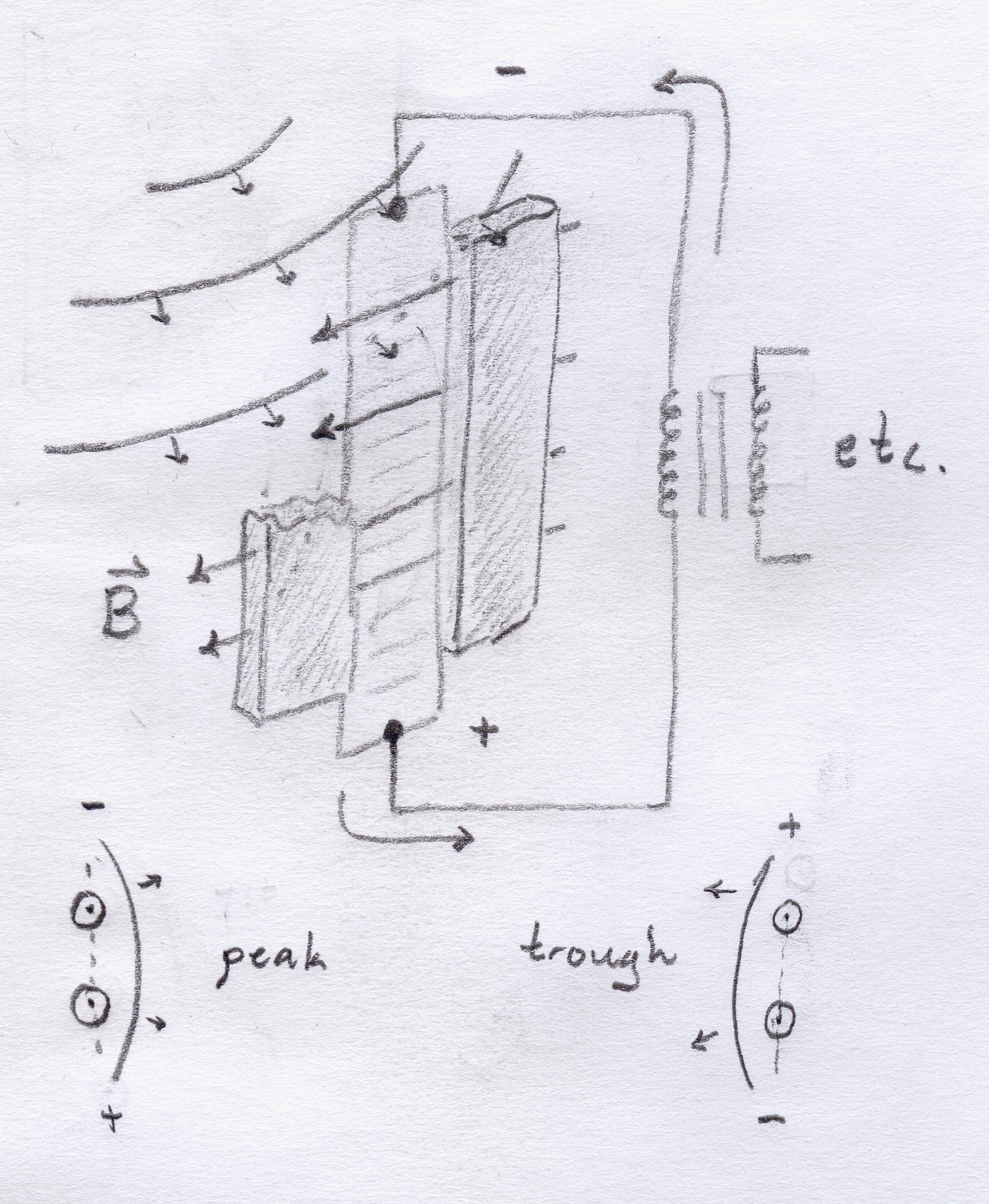

a ribbon mic motor (the term for the bit that picks up sound) consists of a gossamer-thin strip of corrugated aluminum slung loosely between two powerful magnets (or, equivalently, ferrous pole pieces). when sound reaches the motor, the ribbon bends along the corrugations — which moves it across the magnetic field it's sitting in, generating a small potential across the ribbon which runs off to the preamp.

-

the signal out of the ribbon is tiny: i wound up with a

relatively high-output ribbon, which provides about 200 μVpp

when i speak assertively into it. this is easily swamped by

electrical noise, if you happen to live in an electrically

noisy apartment.

ham s will look at me like i'm a wuss... which, basically, i am: microvolts can absolutely be amplified without a lot of noise. however, for a ribbon mic, you have to do so across three decades of bandwidth and can't selectively filter out line hum because it's within your target band. horowitz & hill have a good treatise on how to build an amp that can pull this off, provided you have sufficient shielding (which i don't). - the ribbon itself is exceedingly delicate: modern ribbon mics use 2.5 μm or 6 μm aluminum for the ribbon, which breaks very easily. those foil gauges are not particularly available, either, so i had to make do with something even worse. more on that later.

- the ribbon has very low resistance (around 500 mΩ for mine). this may seem like a good thing, but it means that the slightest stray resistance in the ribbon mounting setup will appreciably decrease your output if you have a reasonably well-matched preamp. this is probably the least problematic of the three, though.

mechanical

i think this is a sensible place to start. many of the design decisions for this mic were a direct consequence of the mechanical constraints of the microphone, including what parts i could actually find.ribbon material

i decided to use imitation silver leaf (also known as signwriter's leaf, at least to some audiophiles on the internet). it's made of nearly pure aluminum beaten around 0.5 μm thick, approxmately the same thickness as the ribbon used in very early commercial ribbons. (and perhaps some modern ribbons, though i would be surprised.)i would have used 2.5 μm 1000-grade aluminum foil, but the only quantities easily available on the internet are small, expensive, 6-by-12 cm rectangles sold specifically for reribboning microphones. since i had an interest in keeping this microphone cheap and repeatable, i wanted something a little more reliable as a source. so, naturally, i turned to alibaba. after speaking to around eight suppliers, i found that either:

- they had 2.5 μm foil in 8011 only, which i didn't want due to the increased resistivity of the alloy,

- they said they had 2.5 μm foil in stock, but actually didn't when pressed (the majority of responses), or

-

they could custom-make 1000-grade 2.5 μm foil, but had a

moq of 10 metric tons... which, according to a quick back-of-the-envelope a friend prodded me to do, is probably more foil than has been used in all ribbon microphones since the beginning of time.

ribbon corrugation

the ribbon in the mic has to be lightly corrugated to help it both hold the correct tension and move when under that tension. this, naturally, requires you to corrugate the ribbon. for some reason, i feel the need to point out that this was an attempt at humor.

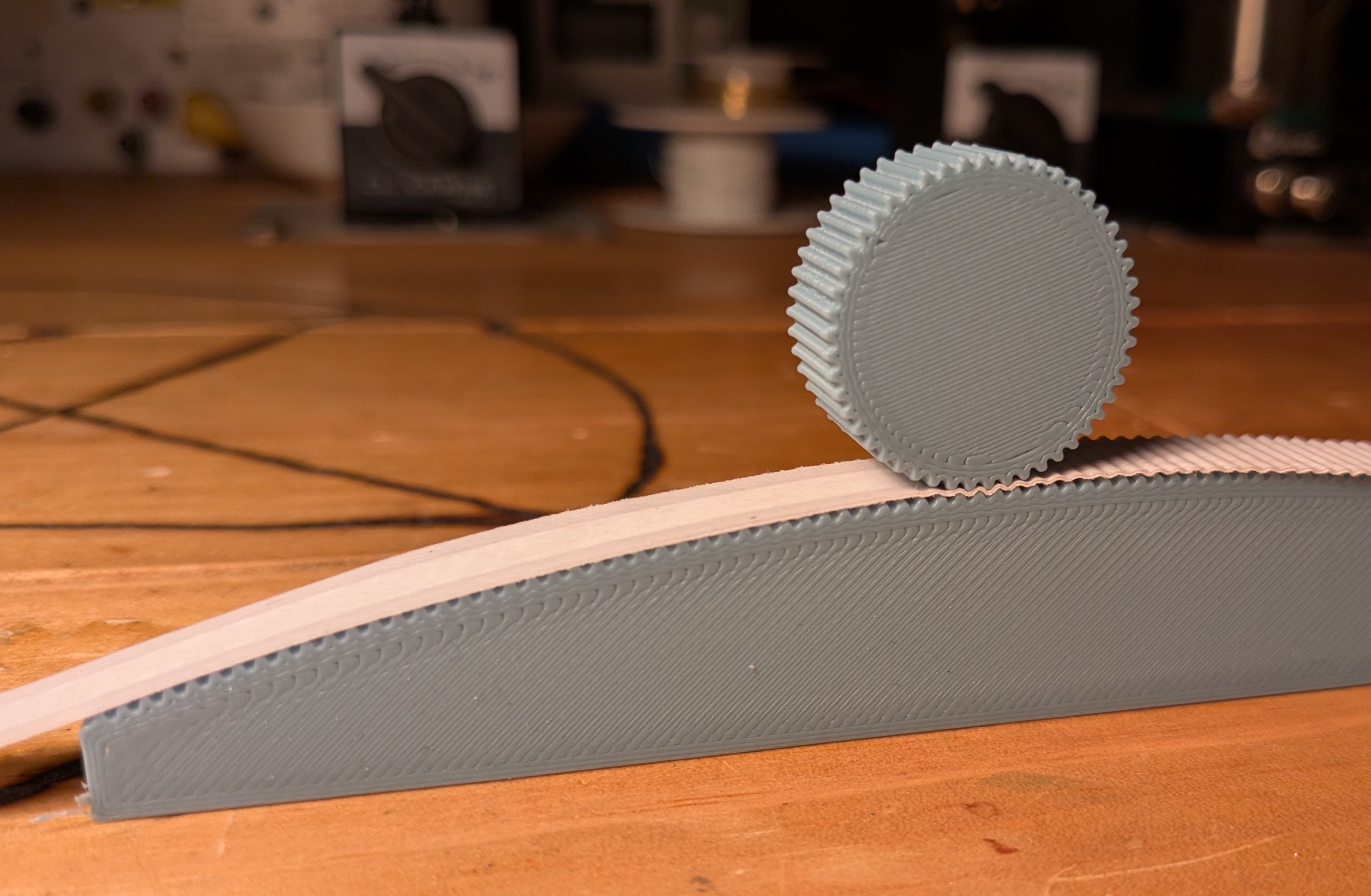

the basic procedure (at least for avid hobbyists) is (a) print some

fine-pitched gears, then (b) run a cut ribbon between those gears. this works

great with 6 μm foil, pretty well with 2.5 μm foil, and destroys 0.5

μm foil instantly — signwriter's leaf is fragile enough to break if

you're brutish enough to touch it with a finger or blow too hard at it, much

less callously mash it between coarse 3

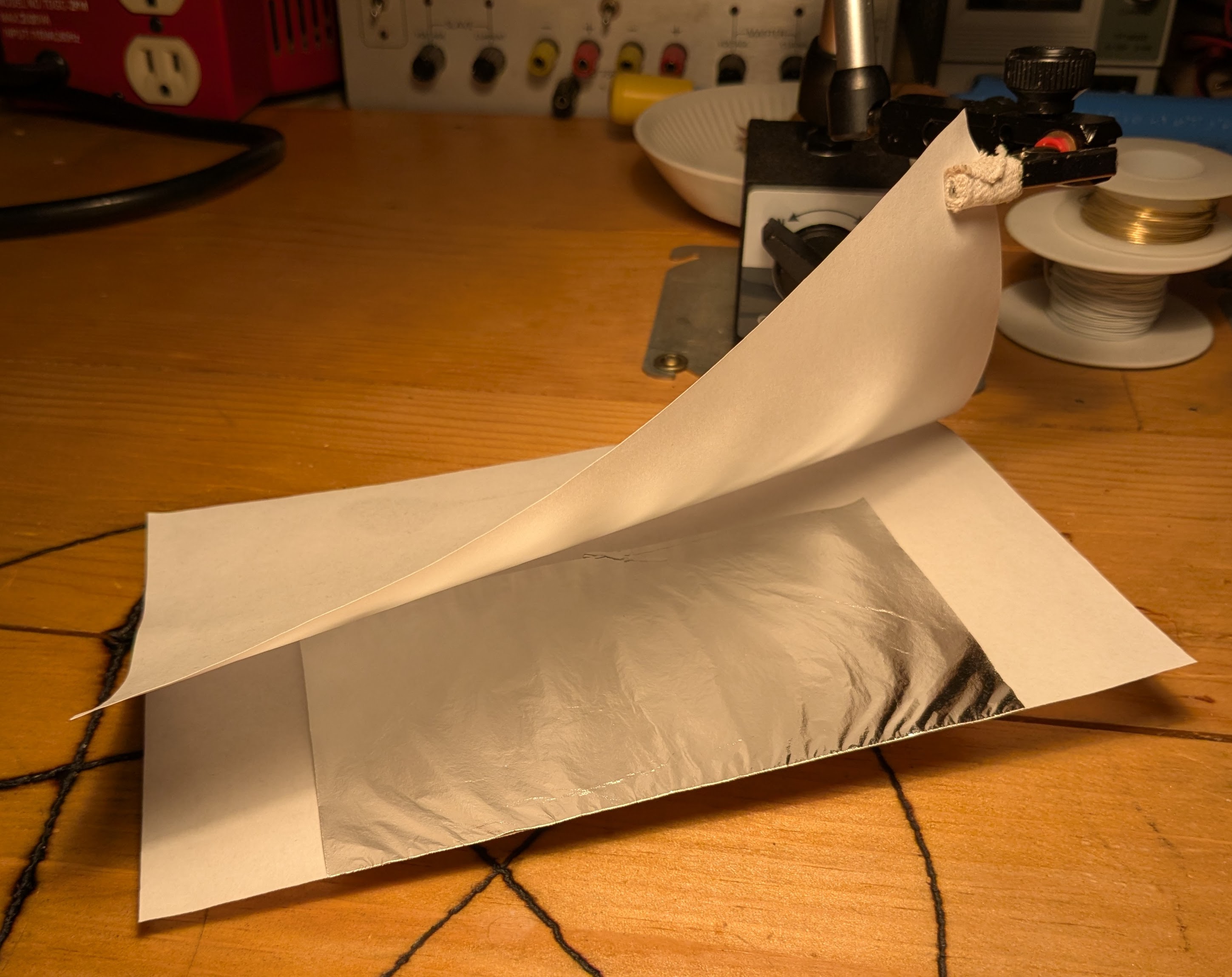

- superglue two sheets of printer paper together. these will form the sacrificial shield inside of which the leaf will live.

- carefully place a single sheet of leaf between the sheets of paper. you will have to directly handle the leaf for this... but fortunately do not have to do anything precise to it, so use cotton gloves of the sort often found alongside this leaf. place it approxmately square with the edges of the paper shield.

- slice the shield with a rotary paper cutter at a known width such that the slice cuts through the leaf. this will give an easy reference for getting leaf strips of the right width.

- shift the leaf/shield combo 5 mm (if you're me) and slice again. this will give you a strip of leaf sandwiched between two strips of paper.

- cut two strips of paper long enough to completely enclose the leaf, and as wide as the gears you're using. soak both in isopropyl alcohol and lay it perfectly flat on a table.

- remove one of the shield strips from around the leaf, press the leaf into the soaked strip, and carefully remove the remaining shield strip from the back of the leaf. press the other soaked strip onto the first strip. they should stick together just enough to allow you to pick up the sandwich, leaf inside.

- run the entire sandwich through the gears to corrugate it. don't be afraid to press hard: “the ribbon can sense fear,” and it takes some force to get the stack to fold enough, especially with fine-pitch gears.

- wait for the sandwich to dry. gross.

- once dry, carefully i write that a lot, don't i? it's a project that requires care in every aspect. peel the top strip of paper away, then very carefully take a pair of flat-tipped tweezers and remove the now-ribbon from the other strip of paper. bending the second strip in a curve right where the ribbon cleaves from it can help cajole shy ribbons into separating without breaking.

magnets

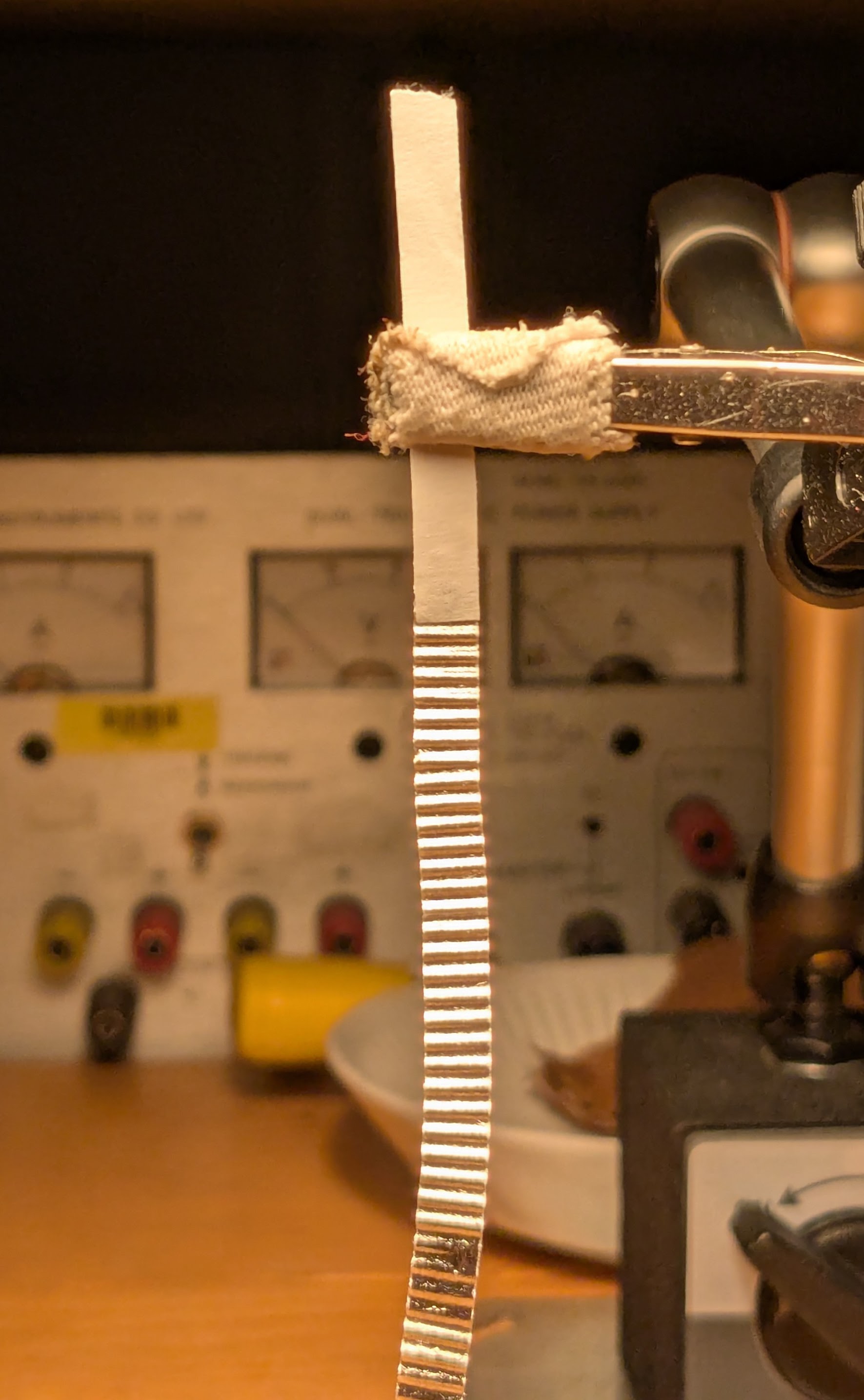

use the strongest bar magnets you can find. they don't appreciably slow the ribbon, and the more flux you can pack into the gap, the higher the output of the microphone. i used two 5 by 10 by 60 mmholding the ribbon

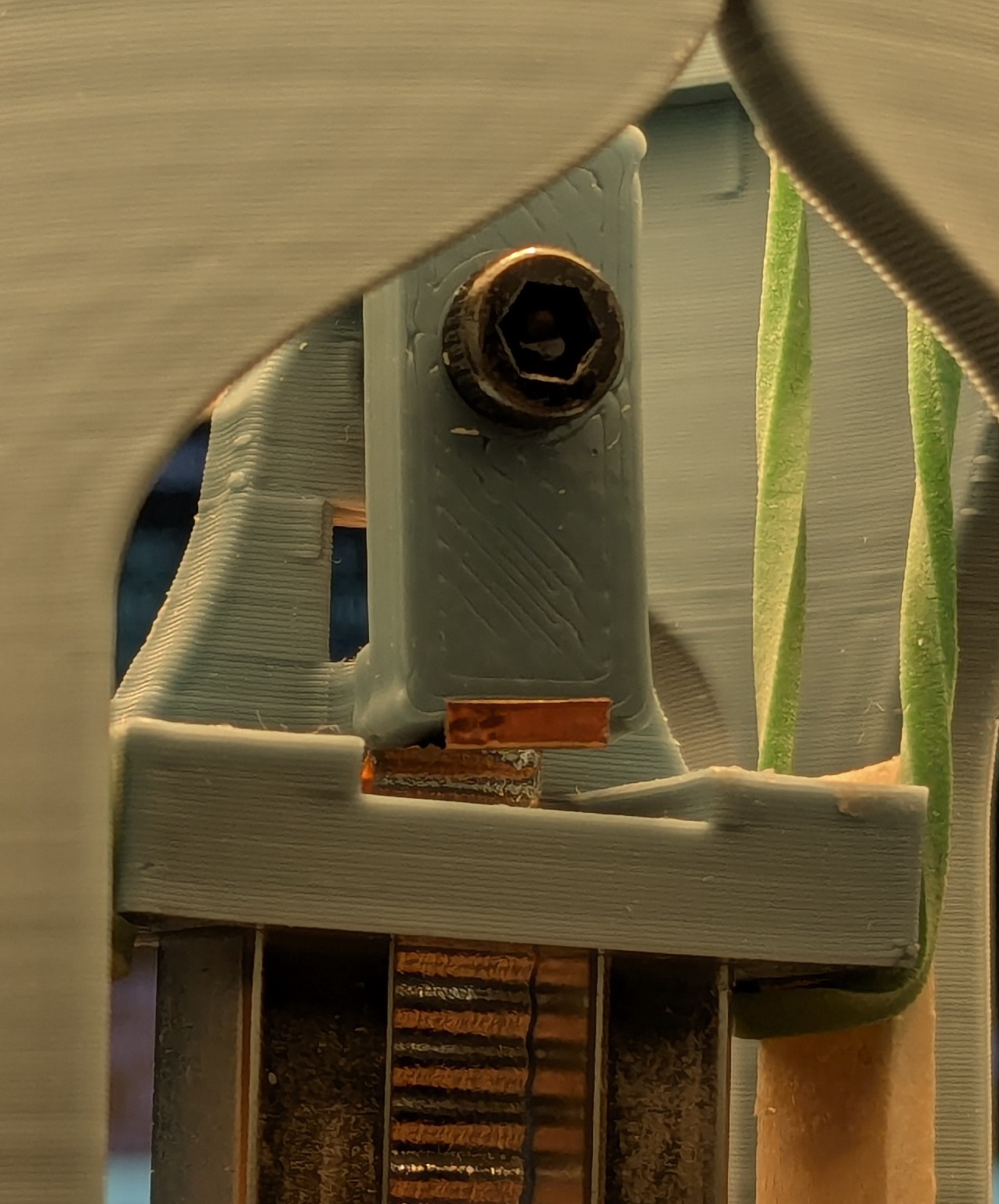

the key is low impedance. here i am doing the ee thing of using impedance when i really do mean resistance. the ribbon itself has a resistance on the order of a hundred microohms, which becomes on the order of a hundred ohms on the other side of a 1:31 step-up transformer. any stray resistance in the mounting armature will reflect to (potentially) hundreds of ohms, which tends to have a deleterious effect on low-input-impedance preamps. this is not, however, a difficult problem to solve, so i will simply provide a terrible photo and explain it.

this scheme allows for both single-screw adjustment of the clamping force and minor adjustment to ribbon positioning via subtly rotating the C, which is useful to get the 0.5 mm clearance even on either side of the ribbon. its only downside is that, prior to clamping, the ribbon must be threaded through the hole in the back plate (just visible in the photo) so as not to interfere with the screw.

electrical

where the magic happens!

i don't have too much more to say other than i needed an active preamp because

my

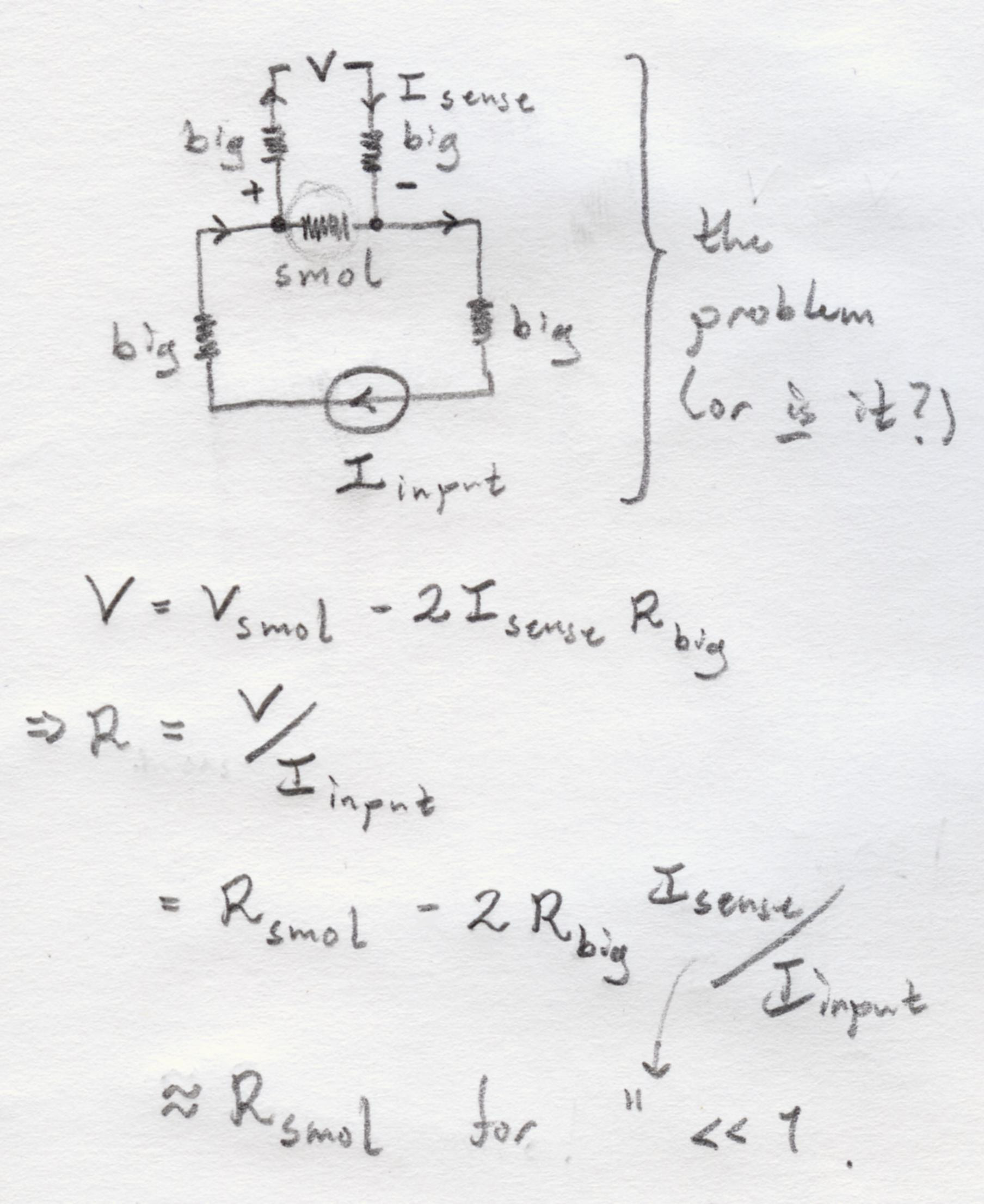

resistance measurement

how does one measure a 500 mΩ resistor accurately? using four wires!one of my old lab instructors said “it's never the resistance in the wires.” except, sometimes, it is. measuring resistances that are substantially smaller than the contact resistance of the leads you're using is inherently unreliable using only two leads — even if you measure that contact resistance once, it will change as soon as you re-clip the thing you're measuring!

this is why fancy desktop multimeters have an extra set of inputs. this allows

performing a four-wire resistance measurement, which renders contact resistance

insignificant; so long as the input current is much lower than the sense

current, there will be no appreciable voltage drop at the point of contact on

the sense line.

transformer & preamp

i didn't follow horowitz & hill's proposition, and used a transformer to make the requisite low noise floor easier to achieve. most likely this only somewhat helped, because my apartment has no earth ground and i suspect much of the noise i'm seeing is magnetic interference from my other equipment, but whatever.

my preamp consisted of a lundahl

results

informally: the damn thing worked! and sounded good, too: comments from folks i know centered around “it sounds like i'm in the room with you.” it also picked up my relatively deep voice well, which i'm really happy about — ribbon tensioning is apparently an art and i am an engineer, so i'm glad i got it close to right after a few tries.further things to try

if anyone wants to:- see what happens with different foil thickness (of course),

- try different ribbon geometry (maybe narrower would raise the output higher, due to higher flux density?),

- come up with a better method of hum cancellation for the ribbon leads, such as running a thin wire right next to the ribbon,

other resources

i exported ani'm looking for work! i have a formal background in electrical engineering with professional experience in software, firmware, & fabrication — and enjoy all of it. if you have work that spans software to hardware, full-time or freelance, email me at work@khz.ac.